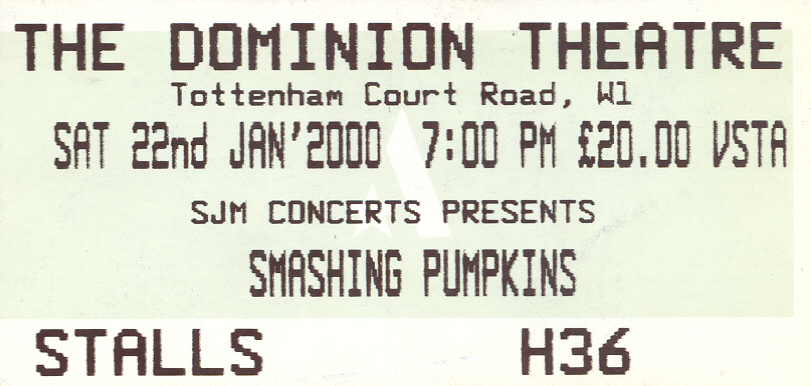

It carried the brace of a challenge that was still alive and kicking, an aspect she might have expected still from Trent, but not Billy, that all was emptiness inside. This was the set. It opened (after the instrumental) with “The Everlasting Gaze”, which culminated in what was nearly a scream, “You know nothing!” (Since the video for this was produced in London that January, its sense is close to the mark.) She later realized this was dualistic, which carried the tone of the whole performance. Then it was guns blazing even more than before, as in this was what she was dealing with (sweetheart). She even began to speculate (as of “Heavy Metal Machine”, probably) as to whether the crisis she was in, in terms of the paradox of entering the One being the furthest equivalent of personal isolation was not just reflected and assimilated but something he himself was experiencing. She wondered if the effect was something he hated as much as she did? She felt she’d at least met the challenge by being present in the room, by being able to provide him with the evidence that there was an existing connection (sort of a double edged sword) to Something/someone else, that it wasn’t sublimation into nothing, a recognition this song reached for in existing as a sort of double entendre, at once an address and self-referential. She picked up on his questioning of her very existence in the emptiness, in “I of the Mourning”. After all, for her part she’d delineated the existence of God inside “nothing” itself. He made an acerbic comment to the effect of surely enough time had been spent thinking about it by now, in sorting it out, which just reinforced the sensibility she’d spent her time waffling and wallowing. It was only in having made the fullest effort to contact him that she felt she’d reached the threshold of arriving when and where she was supposed to, that she felt safe. She ended up seeing his pain as her own and made the most of the moment, of encountering and growing truly aware of him for the first time, and meeting him in the context of the troth she’d sent in her mind.

And in that she saw the full dimensions of so many of his words; in some aspects they graduated for her, for tonight she did believe, and she had given him everything. Even if it was beyond her power to ever meet, she had chosen, whatever the consequences; even if none of it was true, even if he broke it all. It felt like falling in love all over again; she knew she could fall and fall hard. Then he entered into a new song, his song of love, “The Crying Tree of Mercury”.

“This is the song I’ve been singing my whole life

I’ve been waiting like a knife

To cut open your heart, and bleed my song to you

I did it all for you, and you and you and you

It was a multiple address, which didn’t make any sense, unless he was addressing the paradox of the One/All, or offering himself in that same context. And if he was to point at her at this moment, he’d be pointing at the one person in the audience who was literally a repository of this brand of perception in whom it was really true; the one in possession of a universal awareness.

This is the sound I’ve been making for my whole life

I’ve been waiting for this night to clear up all the talk

Although I’m selfish to a fault, is it selfish, it’s you I want

He looked over to her, and at that “you” he hesitated in raising his arm, (slightly premeditated), but that “you” was when he pointed directly to where she was sitting. It was sort of the least she’d expect, pretty much incidental, but at least it was “right”. . .)

You, I did it all for you

This love, will stand as long as you

You, I did it all for you

There’s really no excuse, I did it all for you

This love will stand as long as you

There’s really no excuse, I did it all for you

There are the tears I’ve been crying my whole life

Like an ocean of desire, I’m reaching through the noise

Across the dust of time

Within the lilting lies, I am singing out to you”

(The Smashing Pumpkins, “Crying Tree of Mercury”, 2000)

On this night she fully believed him. On this night it was true, and so were they all. For on this night, which was their first encounter, a full commitment had been rendered in the form of a document and had been delivered, and on this night that document equated with his words. She entered this night on the understanding that this could be the only moment where this communion existed, the night where it came the closest to being met tangibly in reality. She had in fact in what she’d written to him, personified herself as the crying tree (based on her inferences of the title tracks), because of how she’d arrived at the element in being resurrected, and her present state of mind. But as he was the figure crying in this song, he’d imputed that to himself; and for her that was how assimilative this album proved to be. He spoke in her voice; he spoke as her to the point he was her, in the same sum awareness across the spectrum, up to and including the sublimation, sense of isolation and the accompanying pain. It was Alpha and Omega in the prospective sense she’d had of it, before she’d even heard it. It was him. It came from him, rooted in him. He was her.

Then he hit her with one of her oldest fears with “Glass & the Ghost Children” where the lyric she caught was “I wonder if she counts the spiders as they crawl up inside her”, because it harked back to Trent’s use of “insects” in the same allusion on The Downward Spiral. She thought of the analogy in terms of the parable, where the Kingdom of Heaven was like unto a net that was gathered to the shore with many fishes, but once on the shore, many of the fish were thrown back into the sea, a sort that was yet to take place. It was the same with the encapsulating awareness and how she’d expanded it. To have this allusion repeated, and so come across as an accusation from the one she’d asked was painful indeed, when this had already been expressed in its inverse. But at a later interval he announced (a statement she was unable to place) that she had saved his soul.

He sang “I Am One”, introducing it as a return to innocence and the beginning, 1991, for her a landmark year where that had truly been lost as well. But you will note that both in December 1999 and January 1999 this song was going through a lot of variation so it is expected to have been more in this vein and never the same way twice, the improv section of the set, combined with the following, “Rock On“. For his use of the cover “Rock On”, he modified and inserted these lyrics:

“Still lookin’ for that blue jean, baby queen

Prettiest thing I’ve ever seen, baby queen

See her dance on the movie screen”

The rest was shifted and modified to the same target. (She probably misheard “dance” though.)

“Where do we go from here? (sung with complete weariness)

Which is the way that’s clear?”

For her it was conclusive that she’d met her course, and there she reiterated her choice. She prayed God would grant that it could be the beginning, whatever the consequences. Next was “Zero” (the line was still being sung past tense, with the additional twist of “and God is empty, just like you” shouted at the audience entire, –not himself anymore). This was followed by “To Sheila”.

It was during “Cherub Rock” that everyone again stood and she noticed Simon le Bon across the aisle. “Ava Adore” came across as the full tragedy of the dichotomy, far away, so close, interesting because he’d shifted the elements that had been present into the past tense, meaning it would soon be no more, “in you I felt so dirty, in you I crashed cars, in you I felt so pretty, in you I tasted, God” (uttered in a low guttural drawn out growl of the word). At the reprise he began counting, pointing at the ceiling, “I’m counting stars, see?” –and then continued pointing randomly into the audience. (“Stars” remained in the present tense.)

That had been the goal of the redemption, that multiplication, something she’d already written about and delivered. He concluded by shouting “you are all my whores” in full irony, which she saw as full sublimation into the abstraction of the One as the audience at large, irony which could not be more complete since the song was addressed to his intended. So Ray saw him as trapped in the same way she felt trapped. She was there to break it. She witnessed him lose himself there the same way she did, and to her the pain seemed mutual. That he’d lost hope, and was as terrified, as she was.

The closure was the utterly heartrending “I of the Mourning”, which captured the paradox of the existing feedback loop through the radio, where he spoke of kneeling to it, the essence of why he felt trapped as a machine, his only access via technology. Would it save him to know there was a reality behind it? She prayed to God, Will You let it save him? Will it come to this? Don’t let this happen when all he wants is real, really exists. But she felt she was witnessing an individual who had lost hope, when what was denied she had already given. His last demand, “What is it you want to change?” had a very simple answer.

There was “1979” and then the final of finalities, “Bullet with Butterfly Wings”. It was something that stunned her by way of omission because she hadn’t listened to it in all those years. There were times when things that had long been articulated and made no sense suddenly fulfilled themselves with stunning clarity in a moment; this was one.

Tell me I’m the only one

Tell me there’s no other one

Jesus was an only son

Tell me I’m the chosen one

Jesus was an only son for you

(And I still believe that I cannot be saved)

In retrospect, the timing was something else, because this album had been released nearly to the day of when she’d shut it down “forever” and set up the redemption, only to be met by Christ. And so here it was; she stood before him having written of the redemption and delivered it; met him with the applied dynamic of Christ, her reception of Grace. And on this night she’d articulated what had already been her choice; she’d chosen him. To realize as he sang it for the encore, that this was what he’d demanded and juxtaposed with salvation (or the lack of it) years before was something of a shock. In the sense of how her encounter with Christ had been affirmed throughout the entire universal, Jesus had been an only Son for her, and that was what she had brought to present him.